Violence including knife crime, is a major public health concern - it affects many peoples’ lives each year, through death, injury, and detrimental impacts on physical and mental health.1 It also places a significant burden on local and national economies with some estimates suggesting the global costs could be as high as 11% of the world’s gross domestic product.2 Using a public health approach to address violence reduction has become the model of choice in many jurisdictions and is built on a cycle of four repeating steps: surveillance, identification of protective and risk factors, implementation of beneficial interventions and developing and evaluating those interventions. These four strands are guided by a social ecological model that seeks to explain why some populations are at greater risk of violence than others. The model stimulates consideration of risk and protective factors at the individual, community and societal levels.

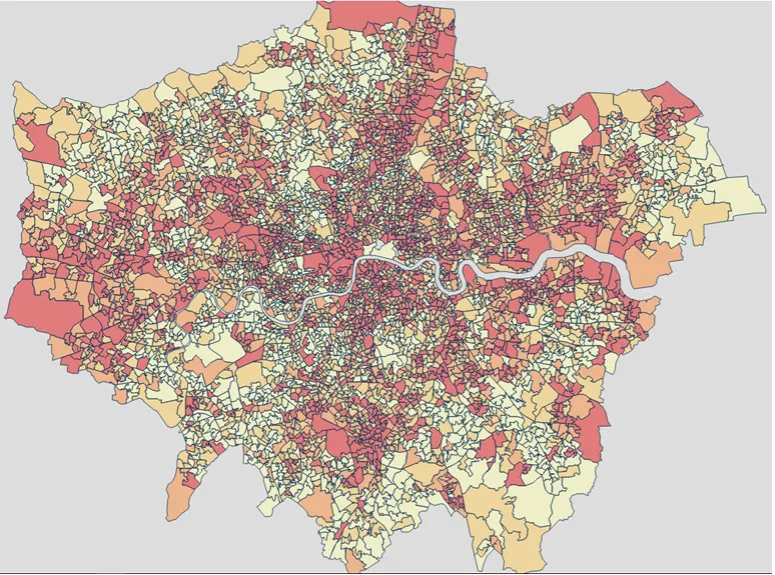

However, recent research has raised questions that should prompt a review of where and how to apply this approach. There is emerging evidence that applying this structure and model to counteract growing trends in violence across a whole metropolitan or local authority area is not the most effective way to target investment and interventions designed to reduce violence, as violence appears to be concentrated in pockets within wider communities and areas.3,4 In a recent study we examined a London-wide picture using Local Super Output Areas (LOSAs) – comprising between 400 and 1,200 households - and have a usually resident population between 1,000 and 3,000 persons as our base unit of data collection and analysis, rather than starting from a relatively limited sample of areas within London, as previous studies had done. We found significant variation in the incidence of violence and violent crime within the whole Metropolitan area, within local authorities and within communities. To do this we analysed a range of datasets that are commonly used to measure vulnerability to violence.

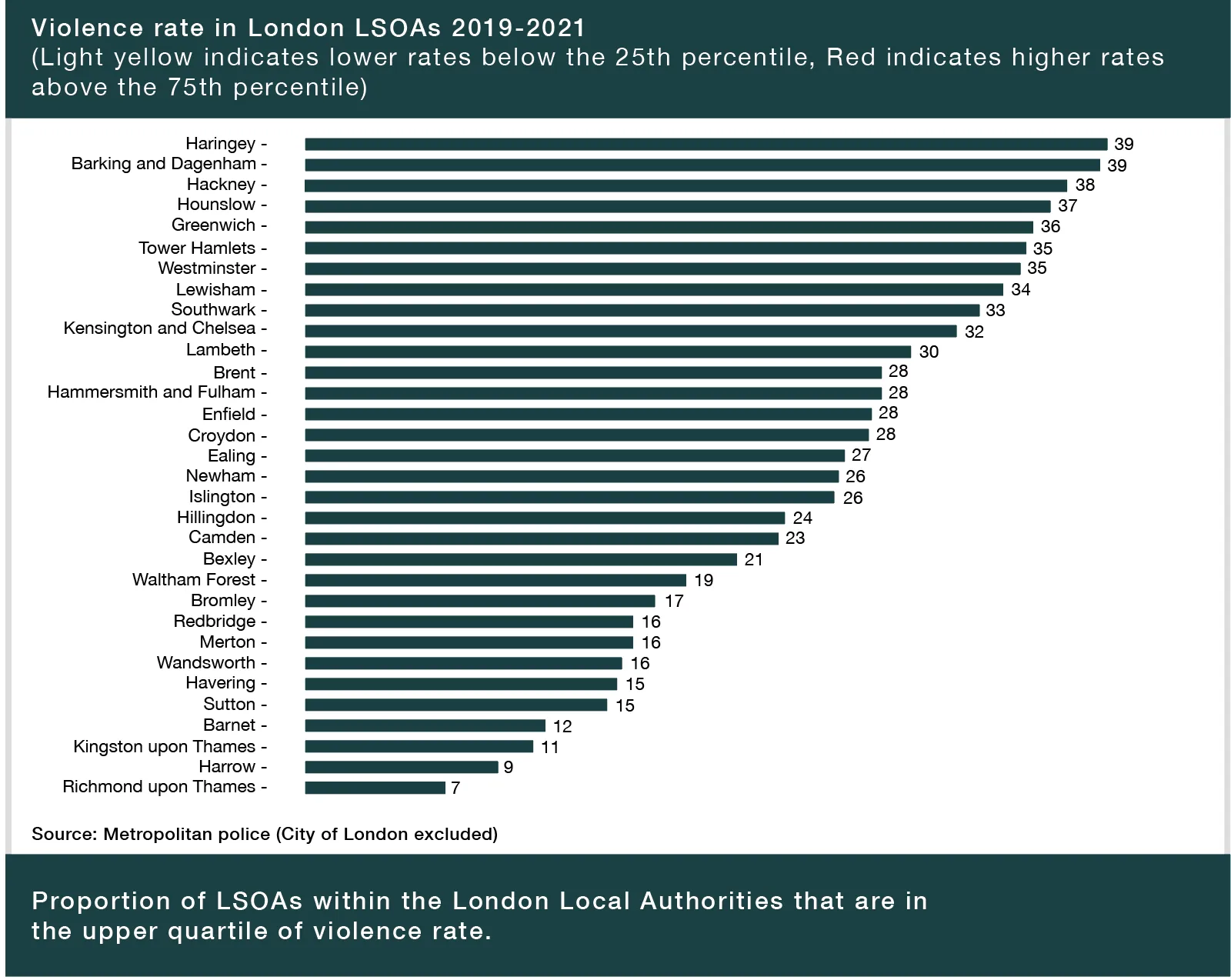

These include deprivation and other societal and economic data, health (hospital, ambulance and Public Health England, education data including Schools Health Education Unit survey (includes pupils, parents, perceptions, lifestyle), Crime Survey of England and Wales, Police Recorded Crime, community infrastructure investment, alcohol use, transport, accommodation patterns, night-time economy activity and alcohol licensing patterns and density. We collated and analysed these data to identify distributions and trends. We examined the correlations between individual or combinations of factors that appeared to be linked to high and/or rising levels of violence. This allowed us to complete cluster analyses to identify LSOAs that appeared similarly vulnerable to violence. We found that violence and violent crimes were clustered in a small number of LSOAs. We selected nine areas for more detailed qualitative and quantitative study. As a starting point for the identification of the nine target areas we used Sutherland’s definition of neighbourhoods vulnerable to violence i.e., neighbourhoods that have levels of violence significantly above average, specifically those in the 75th percentile or higher compared to the rest of London in a given year (ibid).In addition, we also looked at a mix of the areas identified to include LSOAs with a high and increasing violent crime trajectory but also other LSOAs with lower but still relatively high rates of violent crime – the final nine areas were all in the 90th percentile of violence in London.

We found that many of the same drivers that have featured in violence research over a long period – e.g. socio-economic deprivation – remain key correlates but also some new areas, such as universities as vectors for violence and exploitation and the need for greater integration of data across agencies at a much more granular level than is currently the case to enable better analysis of violence in communities and plan with them for change.5 We also carried out local social media posts analysis and ‘community in-box’ surveys within the nine areas. The qualitative data drew a picture of, amongst other issues, initiative fatigue, poor intervention resource targeting, dysfunctional housing policy and practice and poor environmental design, as perceived drivers of violence and violent crime within the nine LSOAs. They also identified potential positive approaches including early-intervention programmes, real co-production of solutions with affected communities and cross-agency partnership building.

Whilst the public health approach to violence reduction has a key role to play it has to date been generally applied to whole cities or counties. Our research indicates that this may not be the most effective way to target resources, and that the focus should be at a much more granular level that better targets interventions and investments into the areas where they will have most impact.

Eddie Kane, Professor, Centre for Health and Justice, University of Nottingham, co-authors: Jack Cattell, Get the Data Ltd. & Jon Parry, Workforce Trust

Further Reading

[1] WHO Violence Prevention Unit: approach, objectives and activities, 2022-2026:

https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/who-violence-prevention-unit--approach--objectives-and-activities--2022-2026: (accessed 14th November 2022)

[2] Benefits and Costs of the Conflict and Violence Targets for the Post-2015 Development Agenda Consensus: https://www.copenhagenconsensus.com/sites/default/files/conflict_assessment_-_hoeffler_and_fearon.pdf

[3] Violence in London: what we know and how to respond; Weishmann et al 2020

https://www.bi.team/publications/violence-in-london-what-we-know-and-how-to-respond/

[4] Sutherland, A., Brunton-Smith, I., Hutt, O. & Bradford, B. (2019) Violent crime in London: trends, trajectories and neighbourhoods. College of Policing 2019: https://www.bi.team/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/BIT-London-Violence-Reduction.pdf

[5] Neighbourhoods Affected by Violence. Kane et al for Mayor of London Violence Reduction Unit 2021: https://www.london.gov.uk/programmes-strategies/communities-and-social-justice/londons-violence-reduction-unit/our-research

Editor’s Note: the reports referenced in this article are also available on www.fightingknifecrime.london/resources