The UK's approach to knife crime has reached a critical juncture. Despite decades of policy interventions ranging from enforcement crackdowns to Violence Reduction Units, knife offences continue to claim young lives whilst generating headlines that demand political action. The Labour government's ambitious pledge to halve knife crime within a decade represents both recognition of the problem's severity and acknowledgement that previous approaches have proven insufficient. However, achieving this goal may require a fundamental shift in how we understand criminalisation itself - one that moves beyond individual pathology to examine the institutional processes that systematically channel certain young people toward criminal justice contact.

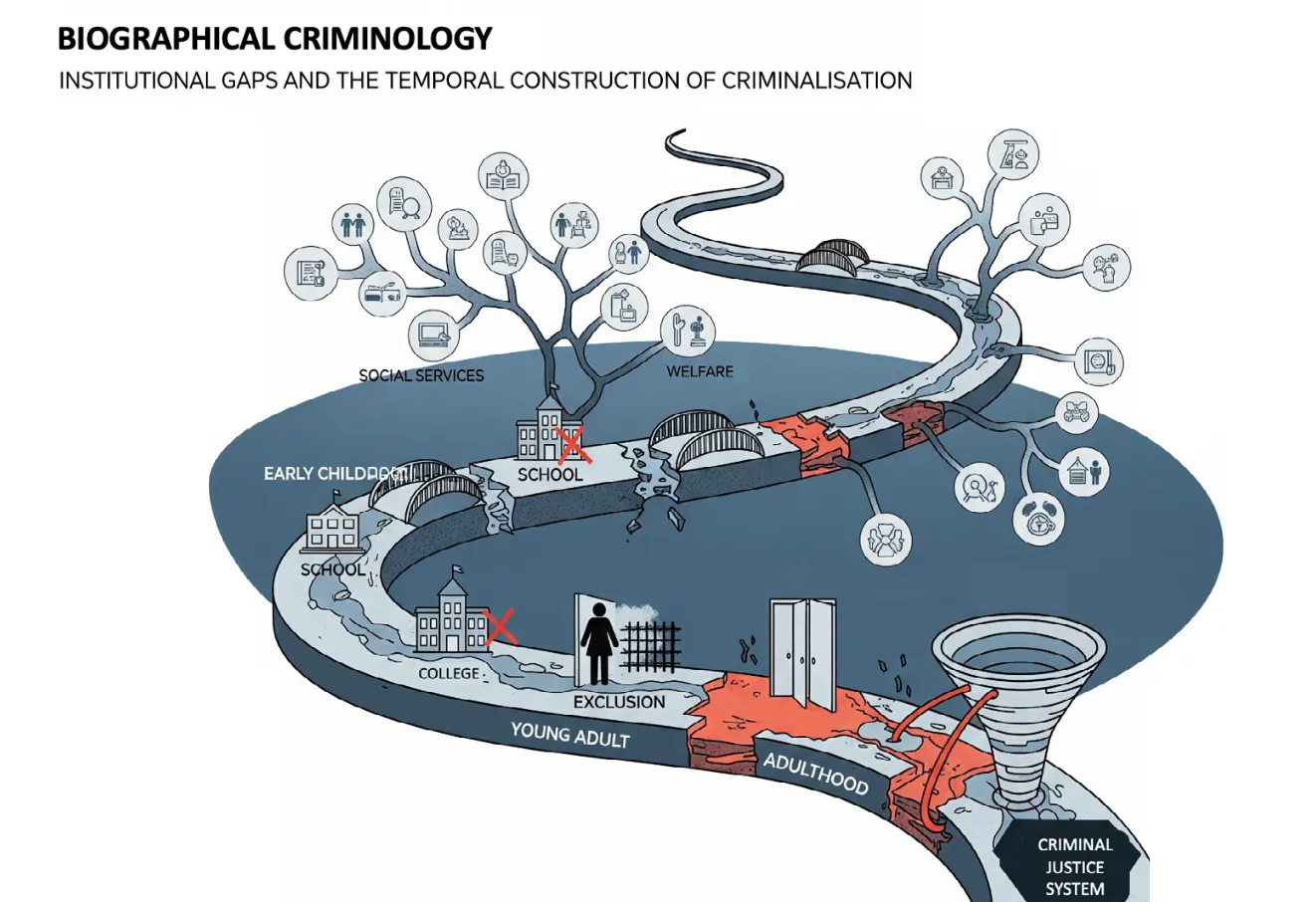

Biographical criminology1 offers precisely this alternative perspective, presenting compelling implications for knife crime policy that extend far beyond current intervention strategies. Rather than treating criminal justice contact as the starting point for analysis, this approach examines the institutional failures that precede and produce such contact, revealing criminalisation as the predictable outcome of systematic gaps in education, healthcare, social services, and welfare provision across individual life courses.

The Institutional Pathway to Knife Crime

Current knife crime policy discourse typically focuses on deterrence, enforcement, and individual rehabilitation - approaches that, whilst necessary, are insufficient because they assume criminalisation results from poor choices requiring correction or punishment. Biographical criminology suggests this framing fundamentally misunderstands the problem. Instead of asking why certain young people carry knives, we should examine how institutional arrangements systematically create biographical trajectories that make knife carrying appear rational or inevitable.

Consider the evidence on educational exclusion and knife crime. Research reveals that young people excluded from mainstream education face dramatically elevated risks of criminal conviction, with each exclusion creating cascading disadvantages that persist across decades. Children with unrecognised neurodisabilities - particularly those with brain injuries affecting behaviour - are systematically excluded from education without appropriate support, creating what I term "biographical injury" that accumulates over time.

This temporal dimension is crucial. A young person excluded at age 14 doesn't simply return to education two years later as if nothing happened. Instead, exclusion creates fragmented educational experience, limited qualifications, restricted employment opportunities, and social isolation from prosocial peer networks. These accumulated disadvantages interact with existing vulnerabilities - frequently including unrecognised learning difficulties, family instability, mental health problems, and experiences of trauma - to create biographical trajectories characterised by institutional rejection and limited legitimate opportunities.

Within such contexts, knife carrying may represent not individual pathology but rational adaptation to circumstances shaped by institutional failures. Young people experiencing repeated institutional rejection whilst facing threats in their neighbourhood environments may view knives as necessary protection when legitimate institutions have systematically failed to provide safety, support, or meaningful alternatives.

Beyond Early Intervention: Preventing Biographical Injury

Biographical criminology insights suggest current early intervention approaches, whilst valuable, remain fundamentally inadequate because they focus on individual risk factors rather than institutional processes creating biographical vulnerabilities. This perspective points toward what might be termed "institutional prevention" - reforming the systems that systematically create trajectories toward criminalisation rather than simply managing their consequences.

In education, this would mean moving beyond behaviour management approaches toward systematic recognition and support for neurodisabilities that often manifest as behavioural difficulties. The framework highlights how children with brain injuries affecting behaviour are routinely excluded from mainstream education without appropriate assessment or support, creating trajectories toward criminalisation that could be prevented through different institutional responses. This suggests policy priorities including mandatory neurological screening before educational exclusion, specialist support programmes for children with brain injuries, and recognition of traumatic brain injury as a specific category within Special Educational Needs frameworks.

Similarly, this approach reveals how gaps in mental health services create biographical vulnerabilities that may not manifest as criminal behaviour for years or decades. Children experiencing mental health difficulties who cannot access appropriate support often experience educational disruption, family stress, and social isolation that compound over time. By adolescence, their presentations have become too complex for single-issue services to address effectively, often resulting in criminalisation when other institutional interventions have been exhausted.

Rethinking Violence Reduction Units

The UK's Violence Reduction Units represent one of the most promising developments in knife crime policy, adopting public health approaches that recognise violence as resulting from complex social determinants rather than individual pathology. However, biographical criminology suggests VRUs could be enhanced by incorporating systematic attention to institutional processes creating biographical vulnerabilities.

Current VRU approaches excel at identifying risk factors and implementing targeted interventions, but they typically focus on individual change rather than institutional reform. This perspective suggests the need for systems change rather than optimisation - we need to change how systems operate with one another and for their clients. Systems need proper funding, but so does systems change itself, and so does investment in systems leadership.

This might involve VRUs conducting what could be called "institutional audits" examining how local education, health, and social care systems respond to young people with complex needs, identifying gaps that create biographical vulnerabilities, and advocating for systemic reforms rather than simply developing interventions to manage their consequences. Such approaches would emphasise preventing biographical injury rather than treating its symptoms. Crucially, this represents a fundamental shift from trying to optimise existing systems to transforming how institutions relate to each other and to the young people they serve.

Reforming Criminal Justice Responses

Perhaps most fundamentally, biographical criminology challenges the assumption that criminalisation represents appropriate response to institutional failures. When young people carrying knives have extensive histories of educational exclusion, mental health service rejection, family instability, and limited legitimate opportunities, criminalisation adds another layer of biographical injury rather than addressing underlying problems.

This suggests criminal justice responses should be systematically redesigned around biographical complexity rather than discrete offending behaviour. Rather than focusing on punishment or individual rehabilitation, responses might examine how institutional failures contributed to circumstances leading to knife carrying, with interventions designed to address systematic gaps rather than individual deficiencies.

The emphasis on "habilitation" rather than "rehabilitation" is particularly relevant here - building on Pat Carlen's insight that most criminalised individuals have never experienced functional social integration requiring restoration. Most young people involved in knife crime have never experienced the kinds of stable educational, family, and community support that protect against criminal involvement. Effective responses require providing foundational resources necessary for legitimate participation in society rather than attempting to restore individuals to previously functional states that may never have existed.

Policy Implementation Challenges

Implementing biographical criminology insights within current policy frameworks presents significant challenges. This approach requires long-term thinking focused on institutional reform rather than short-term interventions demonstrating rapid measurable outcomes. Current accountability mechanisms typically incentivise crisis-driven responses rather than sustained preventive work addressing complex biographical needs.

Furthermore, the emphasis on institutional interconnection suggests effective implementation requires coordination across multiple government departments and service providers - precisely the kind of "joined-up" working that has proven difficult to achieve in practice. Successfully translating these insights into policy may require fundamental reforms to how public services are organised, funded, and held accountable.

Toward Systematic Prevention

Biographical criminology offers profound implications for knife crime policy by revealing how institutional arrangements systematically create vulnerabilities that manifest as criminal behaviour years or decades later. Rather than responding to knife crime through enforcement and individual intervention, this approach suggests addressing the institutional processes that create biographical trajectories toward violence involvement.

This represents a fundamental shift from managing crime to preventing criminalisation - from asking why young people carry knives to examining how institutional failures make knife carrying appear rational within certain biographical contexts. Such approaches may prove essential for achieving Labour's ambitious goal of halving knife crime within a decade, requiring sustained commitment to institutional reform alongside continued investment in enforcement and intervention approaches. Ultimately, effective knife crime prevention requires confronting uncomfortable questions about how our institutions systematically fail certain young people whilst appearing to provide universal support.

The challenge now lies in translating these theoretical insights into practical policy reforms that can address the institutional roots of criminalisation rather than simply managing its consequences. This will require both political courage to challenge existing institutional arrangements and sustained commitment to long-term biographical outcomes over short-term administrative convenience.

Professor Stan Gilmour KPM FRSA is a leading criminologist and the architect of biographical criminology, a theoretical framework that examines how institutional failures across individual life courses create systematic vulnerabilities to criminalisation. His work challenges traditional approaches that focus on discrete criminal events, instead revealing how gaps in education, healthcare, social services, and welfare systems compound over biographical time to channel certain populations toward criminal justice contact.

Professor Gilmour's research has particular significance for understanding the institutional pathways that lead to serious violence, including knife crime, with his framework demonstrating how seemingly legitimate administrative processes constitute forms of "biographical injury" that accumulate across decades. His emphasis on temporal accumulation, institutional interconnection, and biographical embedding provides analytical tools for understanding criminalisation as the predictable outcome of systematic institutional failures rather than individual pathology.

Drawing on life course theory, narrative criminology, and institutional analysis, Professor Gilmour's biographical criminology framework has profound implications for crime prevention policy, suggesting the need for "habilitation" rather than "rehabilitation" and institutional reform rather than individual management. His work builds upon critical criminological traditions whilst extending their analytical reach to examine specifically how institutional processes create cumulative harm across individual life stories.

Oxon Advisory (www.oxonadvisory.com) is a specialist consultancy that applies cutting-edge criminological research to real-world policy challenges. The firm works with government departments, local authorities, and criminal justice agencies to translate theoretical insights into practical interventions that address the root causes of crime and social harm. Oxon Advisory's approach emphasises evidence-based policy development, institutional reform, and long-term prevention strategies that move beyond traditional enforcement models to address the systematic conditions that create vulnerabilities to criminalisation.

Prof. Stan Gilmour KPM FRSA, Oxon Advisory

oxonadvisory.com